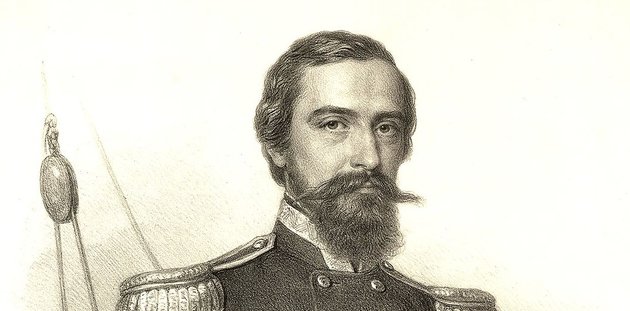

János Xántus (1825–1894) is remembered as one of the most famed Hungarian natural scientists of the 19th century. Becoming a political refugee after the failed 1848–49 Hungarian war of independence from the Habsburg Empire, in the 1850s and early 1960s he was drawn into North American expeditions, and developed a vast network to transfer specimens regularly back to Hungary. Finally returning to Hungary (for the second time), after the Austro-Hungarian compromise (1867) he gained the opportunity during 1869–71 to participate in a series of imperial expeditions to East and Southeast Asia, including Ceylon, Siam, Singapore, Java, China, Japan, Taiwan, The Philippines, and Borneo. The case of Xántus may shed light on how Hungarian colonial knowledge production was embedded in global colonialism.